Ilia Belorukov

Context

When: 24.02.2020

Where: Oslo, Norway

What: Conceptual writing, spies, success, organizing gigs and more

C: Welcome, Ilia Belorukov – from Russia!

I: Thanks, a pleasure!

C: It’s a pleasure having you here! We were just in St. Petersburg together and we came to Oslo yesterday. It’s your first time here. What is the impression of the city?

I: No snow in February. Same… grey! But it was sun yesterday and today, so this is different.

C: But still it’s a different vibe in St. Petersburg?

I: It’s a clear feeling that it is a smaller city. More relaxed people.

C: Let’s start with you telling us a little bit about yourself. Tell us what you do in your musical life.

I: I try to improvise. Something like that. Different sound sources. I try to find something I never heard before. Because it is basically how I explain to myself how I started to play improvised and experimental music. I listened to a lot of music and I felt it should be something else, but I didn’t find it in the music of other people, so I just started to play.

C: In the improvised music of other people, or just the music you were listening to?

I: Just in general, I guess. I mean, I still listen to a lot of blues music, but I don’t play blues.

C: How and when and where and with who did you start?

I: Well, I started to study music when I was 7 or 8 years old, because my little sister started to study in sort of music school called «Dom Pionerov/House of Pioneers», which is a name from the Soviet Union. They are multi cultural centers for kids. I have been there playing chess, and my sister went to piano lessons and musical lessons. And I said I also want to start music, but I don’t want to sing, because there was a choir and choir lessons when you studied piano. So my parents hired a woman from the center who just came to our flat to give me some private lessons for almost two years. Then I went to the center to play acoustic guitar, which I did for about one year, but the teacher wasn’t good for me, probably. I had some pressure and I was afraid to play wrong notes. He was nice guy in a way, and later I played sax in his small band in the center. He told my mom that there is a new saxophone teacher, and he told her I had to go play saxophone, and I said OK.

So yeah, I started saxophone when I was around 10 or 11 years old. This teacher had no experience, it was his first year of teaching. Super nice man, and we still have a good relationship. We played in a band around 12-14 years ago. He mostly plays like progressive rock, fusion and commercial gigs, things like that. So a different kind of music, but he was always open. He gave me some CDs with some fusion stuff, some classical jazz and some contemporary music.

So somehow I started saxophone, and was about there for two years. Then he moved to a musical school in a different district, I went there and it was too far for me, so after about a year I changed to a school in my new district we had just moved to, and studied there. And after some time he also moved there! I studied more or less classical saxophone with him.

While I studied music I also listened to classical rock, then progressive rock, then avant-rock and then New York downtown and from there I found this connection to Derek Bailey. When I was 17 I started to play something like improvised music on the saxophone. I also played electric guitar in the last classes at school. Basically it produces sound for me, I can’t understand how to play on guitar – I can’t play chords! I also don’t know how to play saxophone. For me it’s like I play guitar like I play saxophone, like a solo instrument and I play mostly textures, I don’t feel like playing melodies.

C: But you studied classical, so you can read and know your way around the instrument?

I: I can read still, slowly if I practice etudes and exercises. If I compose, I use computer programs and make a tablature and MIDI for the the bass player in my band, Wozzeck. The drummer can’t read, so he translates his parts into his own system on paper.

C: Tell us a bit more about Wozzeck.

I: I studied at the Electrotechnical University for almost 3 years after school. But I didn’t finish it, and switched to music. I started to play on stage and it was in May 2007 I got this gig at Experimental Sound Gallery. This was the main venue for experimental music in St. Petersburg with Andrey Popovskiy as program director. Now it is called Sound Museum and it’s a bit different place. There were some people who had heard my playing and from there it just started to grow, and there was this other band with Mikhail Ershov, bass player, and Pavel Mikheev — a guitar player, but also a drummer — and one other guy, Maxim Pozin. The band was called Dadazu. They invited me to play in this band, and at some point there was an occasion to use a proper studio. One of my friends was a student for sound engineering and she proposed to go to record something there. So I just invited Mikhail and Pavel (who became the first drummer of Wozzeck) on 11th September, 2007. So this first session became our first album called Act I.

Then we played a few concerts with this drummer, but it was a bit difficult to play with him because he had a lot of other projects. We continued as a duo with Mikhail. We played mainly noise stuff, and I played saxophone with a computer and FX pedals, and he played bass guitar with FX pedals. Later we did studio sessions with guests with half-composed pieces, which ended up as the first release «Act III: Comics» on Intonema, which is a label I run together with Mikhail.

After that I had some interest in playing hardcore and metal. I always had interest to heavy music. I showed some ideas to Mikhail, and he also liked this music. We found a drummer from a metal band who also had some interest in some experimental stuff, and also at some point I invited my school friend who was a guitar player, metal guy. We did an album as a quartet, so Wozzeck with metal compositions, noise elements and some drone stuff and some improvisation. This was around 2008/2009, and released around 2010.

C: That’s before Shining (Black Jazz). I haven’t heard this (Wozzeck album), so I don’t know how close it is too Shining’s record. But you have probably heard Shining?

I: It’s too well made for me. It is very good musicians. But I feel it’s too nice. Maybe because I can’t play like that, maybe because it is so well produced in the studio. Maybe it’s different during a concert.

After that (the metal period), we switched to another direction. The new album was called Act 5. For this album I had the idea of 5 tracks, each lasting 40 minutes. Each is different material, textures and structures. When I presented the idea, the guitar player saying it was not for him. Then we worked very intensive with the material for 2 years. After that the guys were really tired from me.

C: Are you a strict bandleader?

I: It was totalitarian. It was my compositions, and I chose literally every sound we would play. When we started on the last piece, the relationship were quite bad already. Finally it was released as one DVD with audio files and FLAC files. We had an idea to make a 5 CD box, but instead we decided to make a proper booklet with explanations, screenshots and some parts of the written material.

C: I never got this from you?!

I: Strange, but next time! We still have some copies. There was no success! But it was an important part for all of us. This last track, which was recorded with everyone in a very bad mood, is probably the most interesting. At least Mikhail says it is his favorite of the five.

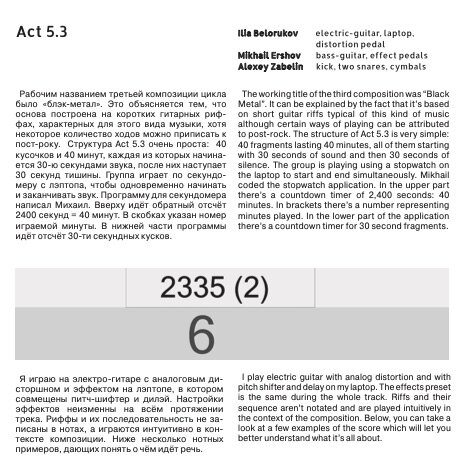

The music on this record is very brainy. The first part is kind of electronic techno style, but it’s not in 4/4 but in different time signatures. The second is almost like metal, hardcore stuff. Third one was probably my favorite. It’s sort of improvised black metal riffs. There are 30 seconds of music, and the 30 seconds of silence, lasting in total for 40 minutes. We played several times at rock clubs. The people were really shocked.

C: It’s hard to get any success with experimental stuff, but do you think it would have been different if you did this thing in another country, like Norway?

I: It mostly depends on promotion, and we had nothing. We released it on Intonema, but it’s a small label. Even people around us, people from the improvised world, couldn’t understand it. Of course, it was too much for the people from the rock/metal scene. For the electronic people it was maybe OK, but it was too much playing on real instruments.

C: So who was it for?

I: It was somewhere between different styles. But it is also one of my ideas to find something between genres. I don’t like to put myself in frames. Of course that happens sometimes. But this is difficult in St. Petersburg and in Russia in general. It’s not possible, because people don’t understand what you are doing. It’s probably the same everywhere.

C: I guess it is more or less the same everywhere, but here, because of funding, it is given a chance to live a bit longer as you can get some money for promotion. There’s a lot of things going on, but it feels like people are more – I wouldn’t say educated — but they know that these experimental things are going on, and although it’s not their cup of tea, they don’t get shocked. Of course it’s not commercial stuff, so you’ll never reach the masses, but there are many venues and festivals where you can present your music, and the audience goes to these places, not because it’s a rock club or a jazz venue, but because of the music presented. The audience is actually decent, but it’s hard to see them all at the same time. They have to choose because so much things are happening all the time. If there were only one or two events every week, then maybe everyone would go there. But now they have to pick and choose.

I: It’s growing everywhere.

C: I also feel like the commercial stuff is growing.

I: For me, this pop culture exists, and people who come to our gigs they really don’t care about it. There is for sure more interest for art and creative arts than before. In case of Norway or other places in Europe, the level of life is higher in general. Therefore people have time to think about something else than just surviving and making money. In Russia it’s probably growing in a more distorted way, because we still don’t have enough money — at least not in the improvised music world. Mostly people just do this like a hobby, and very few people are dedicated to music.

I don’t know if it’s good or bad. I like the passion of some of them, like they really want to do it. But then when you ask them to go somewhere and play, and you say you have to ask the venue for money — at least for travels — they just say «no, no — art is not about money, we just make music».

Everyone wants to find some kind of balance. But after some time, I guess people just started to be disappointed. There is no audience, no money. There is just you and your music, and nobody wants to listen. That’s pretty depressive, so people just stop to play.

C: But you’re also quite conservative in the way you present acts (when you are the organizer). I remember we were talking about this in St. Petersburg. There are other organizers who are doing marketing and promotion in a different way, whereas you are more straightforward. There will be a concert. Here’s the venue and this is the price. And you don’t present the artists at the gig, it more or less just start by itself, right?

I: Yeah, that gig with you and Katariin Raska was without any speaking. I just didn’t feel like I had to talk. Sometimes I do some introductions, but it really depends on the atmosphere and other things. Probably I should do it all the time…

C: Do you think this has something to do with it? That there is a chance to get more people if you market or present it in a different, without selling something that you don’t provide, but making it a bit more accessible?

I: We try to fix this promotion thing, but there is always other people who organize, and they can get more audience, but that audience don’t care so much about music. So I still don’t know if it is better to have 50 people and 40 of them are really not interested, or to have like 20 and 15 of them will be really dedicated. Money-wise, 50 is better…

If you want to get more success, you just have to pay for some professional promoters. But we don’t have any support in Russia, so we can’t really do it. There are quite many festivals now for electronic music and some experimental electronic artists playing there also, but it’s more like rave/techno events. Most of them don’t come to listen, but to dance. The music we are interested in, is still music — you really have to think about it. It’s not only about making fun. You have to know what this is. You have to translate sounds you hear to yourself and find something. Basically, people prefer not to think about serious stuff.

C: I think the setting has a lot to say. If you give people something that they can relate to, then it is easier for them to listen to the music and make something out of it.

I: It could be, but I don’t really know how that works. At this gig (in St. Petersburg), we had some people that I’ve never seen before. How did they know about the concert, and why did they come? It’s a big mystery. There were probably around 30 people, and 10 of them I didn’t know. I’m not sure if they will come next time.

It seems like people also choose based on venue. Like this venue (Masterskaya Anikushina), people like to go there because of the atmosphere of the place. Some people don’t like to go to rock clubs, like the one we played at in November with Ilia, Konstantin and me. This club has a bad reputation among some people because the owner is kind of like a business guy and very clear about what he wants to do. He was always supportive of us. He makes money out of youngsters, rock bands and pop bands, but he knows that there is other music out there which should be presented. So this is good, but some people have some problems with him, just because of some relationships! So people don’t want to go there. But he’s really one of the guys who understand how it works.

I also don’t organize gigs at some places, and I don’t play there because of some other not so good stories happened in the past. It’s local stuff, and it happens everywhere.

C: People also disagree here in Oslo, but it’s such a small city in a way, so we also get a long even though some people don’t have the best chemistry. It is impossible not to meet and we’re organized in the same organizations despite playing different music.

I: It’s because you have rules and traditions for this. It’s about communications. There are several communities in St. Petersburg who play and organize improvised music, but we’re really disconnected from each other. Like, I know some musicians around, but these guys never come to our gigs. We are almost exclusively the only ones who organize for foreign artists who plays improvised music. I can understand if they don’t come and listen to me or other locals, but when we invite big names like Peter Brötzmann for example. You have to learn something from him, just by going to the concert.

C: They can learn something from me as well!

I: Haha, for sure! But Brötzmann is one of the fathers of free jazz! When you play improvised music, you can learn a lot from these people.

But we don’t have this tradition. In the Soviet Union there was nothing. People were afraid of each other because there were spies everywhere. 70 years of this destroyed many things in people’s relationships. Historically, we just started to learn how to talk to each other again. I myself am pretty bad with social life and communicating with people.

C: How do you see that it can be changed? Do you think it would be good with an umbrella organization?

I: I think it is hardly possible at this point. All of us are too egoistic at the moment. I know, there’s an opinion that younger musicians just copy older musicians and that they don’t have their own voice. But how can we get our voice if we don’t share experiences? So it’s also about generations. I think the next generation will be able to communicate better. Or the next after that. Or maybe it’s an illusion.

The generation before me, say the people who are now around 50 years old, they grew up in the Soviet Union. They have a completely different mentality. I was also actually born in the Soviet Union too, so I still have some of that mentality. It is difficult to change. The younger people that I meet now, around 20 years old, they think differently. Maybe more open, but they are also more concentrated on many things, not only music. So music is becoming more and more like a hobby thing.

Touring 10 years ago was much more easy than it is now. I could ask an organizer, and they would organize something. Now there are too many people. Everyone plays, even if it is just as a hobby, and if there are some locals who play experimental music, they would rather organize for them than for someone they don’t know. So you have to be a very social guy nowadays to get gigs.

Making connections on Internet is not the same as real life. On Facebook you have to comment everything, make «likes», and then (maybe) someone will remember you. This system I can’t understand for now. Some people have a «talent» for these things, but others don’t.

C: But hasn’t it always been like this? Facebook is just a different medium, a different platform.

I: It’s true also, but it is more of a caricature for me. Facebook is not real. It’s just somewhere, and we can be completely different there than in real life.

C: A lot of people are good at social media, but not many are very good at social media and also great players. You have to have both of those if you really want to succeed, I think. You have to have some proper content.

I: I don’t know. I still believe in people making music seriously, and people just don’t know about them because they don’t present themselves. Russia is such a big country. I’m sure there are some people who are making something interesting, but we don’t know about them because they are too shy. Maybe the social circles around them don’t accept art. I know a few guys in other cities who did interesting things. I told some of them that they have to record, play around, come to St. Petersburg, stuff like that. But then after some time they just stopped to play, and started something different, like with electronics instead of acoustic instrument playing because there were some more success.

In Russia you really have to be strong to fight the people around you and to protect your music and art. With music it is most difficult, I think, because it is so abstract. I know some guys who’ve had success with visual arts. Probably it’s fair, but because I’m a musician I can’t really understand it. A painting you can just look at for 2 seconds, and make up your opinion. With music you have to concentrate and think about it. When it stops, it disappears. This moment is very strange for me, still. It is the most creative thing, and it is very hidden, somehow.

C: One of the reasons why people don’t pay is because they have access to everything for free on YouTube, Spotify and so on. If people still had to buy music to listen to it, then I’m sure people would buy much more. What is your take on streaming services?

I: I don’t like it. People can listen 2 seconds on the beginning, then 2 seconds at the end… it’s not right. You have to spend some time to think about it. Again about the Soviet Union: We’re still pirates here in Russia, mostly because salaries are still quite low to buy music for American or European prices, especially for musicians. Musicians can’t afford it, so we listen online or download. Now it is better, I think. The younger generation doesn’t know what a CD is.

C: And how is that better?

I: It is better because of the availability of music. You can find and listen to almost every album now legally via Apple Music or other platforms. You don’t have to be pirate with torrents.

With good music you also need to listen on a good sound system. With streaming people just use headphones of low quality in most cases. Pop musicians fit into this format, but that’s not the case for the experimental or improvising musician. If you take Beck or Katy Perry recordings it sounds good one very system. As a sound engineer I like it, but as a musician I think it is very flat, very compressed. There is no difference, and it is very strange.

Maybe people will have more interest in going to concerts because of this. You can’t create a live situation with streaming music. People still need this live energy. Personally I don’t even like going to concerts, honestly!

C: !!!?

I: There were very few concerts I enjoyed when I was organizing. I have a different mood. Also when I go to other gigs, I start to think about other things around, like sound, how it was organized, other professional things.

C: When you are organizing it can be hard to settle. You are responsible for so many things.

I: Yes, I really can’t concentrate well on the music. Another thing is that although people like concerts, they don’t want to pay. They would rather buy a beer, even though the price of a beer is more expensive than the concert.

C: I think that’s a problem all over. Artists are selling themselves too cheap. Of course we want to play, but if we keep doing it without people paying, we’re just digging our own graves. It’s a hard nut to crack. I can’t see the big arcs or big changes since I started, and I’ve been lucky — I’ve got to do a lot of things. But I do see some changes, though. There are some more social and politically enforced motives which changes how things run. We want a broader spectrum of people in the music, and not only music. In general we want more women in the places which have been dominated by men, and the music business is also one of those. We want to make role models and encourage the new generation of girls to play. I feel that has been a central theme which has been going on for a couple of years, and which makes the dynamic of booking gigs and getting around different than how it was before.

Other than that I feel that it is more or less the same when it comes to payment and selling records, as it was around 7-8 years ago when I started out. It’s like you say: there are more musicians, so it’s hard to make a good tour route. You can play a lot, but probably not for money everywhere, and you have to travel more around to get those gigs. I hear stories from the generations above me. They could be in one city in Norway for several nights before moving on to the next city. Now you get a gig in Oslo, then you have to take plane to Munich, and then you go back to another Norwegian city. And that’s not the way you want to do it, but it’s the only way because it’s the dates they can give you.

I: If you have this possibility it’s good. If I go to Berlin I have to organize something around, so that somebody can pay for the travels.

C: That’s also true for us, but we have some funding to make the traveling happen. That is also a little bit like digging our own graves, because the organizers know that we have some support money.

I: Yes. I know I can always invite Norwegians because they can get some support, and the audience will be happy either way. So why should I pay for musicians who are not as good and who don’t have support to travel? They have less gigs, so they will be less experienced.

C: It also says something about the Norwegian government and their mentality. They think that art is important and therefore Norwegian musicians will be much more around than other countries. Hopefully that can teach other countries a lesson. They can see that funding works.

I: I don’t think it is connected that much with support. If you are a good musician you will get some respect. If you’re not an interesting musician, then probably not. My impression is that people knows more Norwegian improvisers. Like, I’m sure there are many German or French improvisers, but people don’t know about them, because they’re touring less. I’m talking mostly about improvised music, electroacoustic field.

C: I feel there are a lot of Germans around!

I: Yeah probably, maybe in other areas that I don’t know.